Many people begin meditation as a wellness practice. Others want to sharpen their focus and enhance creativity. Others are trying to develop a calm emotional bearing. Still others are seeking a pathway to heaven or enlightenment.

Here are a few observations about the four dimensions of human experience, and how a daily meditation practice can help to improve and nurture each of them. Some of what I will share has been documented by research, some is anecdotal and some even speculative. I’ll do my best to make clear what can be substantiated by more than my own hunches, and what cannot.

Meditation and the Physical Dimension

Meditation offers many benefits in the physical dimension of life, and could easily be adopted for the physiological effects alone. It’s one of the most effective ways to clear your body of stress hormones such as cortisol, and to promote the release of positive hormones like oxytocin. Daily meditators report that they sleep better. Meditation has been shown to improve cardiovascular health, and to reduce inflammation and help with pain reduction and pain management. There are also numerous health benefits to be derived from leaving behind the bad habits and addictions which tend to fall away after one adopts a daily meditation practice.

Also in the material realm, beyond the physiological benefits, meditation is often the gateway to better financial well being. Part of this is related to the better physical health, better decision making and better overall function promoted by meditation, but there is also a somewhat inscrutable tendency for things to simply “work out better” for people who meditate. Many people attribute their personal material well being directly to their intentional efforts to help it manifest while in a meditative state.

The practice can help you on the job, as well. Meditators report that they experience increased job satisfaction, better performance and better relationships with supervisors, peers and direct reports.

Meditation and the Emotional Dimension

Meditators report lower stress levels, and better overall emotional health. Studies tell us that meditation increases one’s sense of empathy for others, reduces anxiety, boosts self-esteem and optimism, and helps remove addictions, undesirable compulsions and negative states of mind. Better moods, better relationships, a prevalence of calmness and more joy are commonly reported “side effects” of adopting the practice.

Meditation and the Mental Dimension

Study after study has documented effects of meditation which include improved memory, mental clarity, attention spans and ability to focus. EEGs show more electrical activity in the areas of the brain related to reasoning and decision making. They also show enhanced activity between the two hemispheres of the brain, and globally throughout the organ.

Often, people who meditate report that they seem to have tapped into a wellspring of creativity and intuition that they scarcely knew was available to them before. New insights and solutions to problems seem to come to mind “out of the blue.” Creative people become even more creative. Collaboration becomes easier and more effective.

Better Performance by Any Measure

The effects of a regular meditation practice are profound, whether in the physiological, financial, emotional or mental realms. Once people begin to meditate they are generally more productive, happier, perform better and are more pleasant to be around. Even a quick review of the data confirms all of this, and should be an encouragement to anyone who is considering beginning a meditation practice.

There is yet another dimension to be discussed, though – that of the spirit. It is in the spiritual dimension where meditation proves itself to be not only a useful practice, but a nearly essential one.

Meditation and the Spiritual Dimension

When I use the word “spirituality” it is meant to describe the activities and pursuits in our lives through which we attempt to find meaning and purpose. Whether we are drawn in these spiritual pursuits toward theology, cosmology, philosophy, psychology, sociology, art, religion – whatever the approach – we are trying to determine why we are here, what meaning our lives might have, what legacy we might leave, and how to live the best and happiest life that we can during a relatively brief human life span.

It’s a little more difficult to speak with clarity, let alone certainty, about the effects of meditation in this dimension of human experience, but I shall do my best. Much of what I write falls within the domain of speculation, but I do believe it to be a well informed speculation.

It first ought to be said that the meditation practices that we know, whether focused, mindful or transcendental, all come to us from spiritual traditions. They may be used to good effect by those who have little interest in spirituality, let alone religion or mysticism, but the fact remains that these practices and techniques are rooted in humankind’s quest for meaning – for a deeper understanding of the universe and our place in it.

So it is natural that a meditation practice, whether it is intended to do so or not, may lead one to levels of consciousness where glimpses of “the answers” arise, or at least where a further interest in “the questions” is sparked.

People who meditate often report a growing sense of their lives as part of a unity, or kinship, with other human beings, other sentient beings, or indeed with all things, living, dead, animate and not. I believe that this is because that unity is the fundamental truth, and meditation can bring us into a state of consciousness where that truth is not only evident, but where it is directly experienced.

Meditation also helps to cultivate the qualities of compassion, kindness, forgiveness and joy. Regardless of how one views the “purpose” of life, certainly these qualities are preferable to misery, hostility, callousness, rudeness and holding grudges or seeking revenge.

Meditation also seems to help us get in touch with the passions in our hearts, and helps us develop the courage to pursue them. This is key to finding purpose and meaning.

It is said that when the student is ready, the teacher will appear. I have noticed in my own life and practice that meditation has helped me “get ready” – bringing ideas, resources and assistance to me by happy accidents of synchronicity at precisely the right times during my journey of personal development.

Explorations in the Essential Field

There are those who believe that our minds are structured in very much the same way as that which we observe as material reality. On the surface, things appear and behave differently than what we know to be true when we delve into their essential nature. Moving from the outward appearance of a “solid object” we first see compounds, then molecules, then atoms, sub-atomic particles, and then it gets very strange. As nearly as we can tell, the fundamental essence of things can be described as an energetic vibration, and what is experienced of it depends at least in part on the expectations of the observer. The vast field of probabilities waits until it is being observed before it decides how to express itself. Everything that we experience arises from this field of probabilities. All things arise from no thing.

As we achieve deeper and more profound levels of consciousness during meditation, it has been speculated that we can experience this field, and interact with it – perhaps even influence it – more directly than we do when mitigated by our bodily senses. Since the field is the foundational essence of all time and space, it is boundless. While experiencing these deeper levels of consciousness, we, too, become unbounded.

Stories of the great masters and saints who performed amazing feats (miraculous healings, being in two places at once, accurately predicting the future or giving witness of events which are happening great distances away, etc.) suddenly make more sense in this context.

When we meditate, do we really gain access to all of the wisdom and power of the universe? Do we encounter the face of God?

For many, many spiritual seekers over many thousands of years, that has certainly been the primary goal of the practice.

Calmer, Kinder and Better, At Least

Tempting as it may be to adopt the practice of meditation in hopes of attaining sainthood or supernatural powers, I shall be happy if it helps me to become, simply, calmer, kinder and more able to cope with the challenges of life in the coming decade or so.

It seems to me that this is reason enough to set aside a little time each morning and evening to practice.

I’d love to hear your experiences and thoughts on the matter. Please get in touch by email, or leave a comment below.

It strikes me that one of the most important things to bear in mind when beginning any spiritual practice, but particularly meditation, is the word “practice.”

It strikes me that one of the most important things to bear in mind when beginning any spiritual practice, but particularly meditation, is the word “practice.”

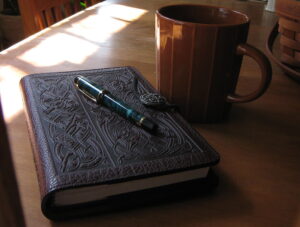

One of the very first things that I learned to do when I began to change my life was to begin keeping a gratitude journal. This incredibly simple practice can have a profound effect on one’s happiness and well being.

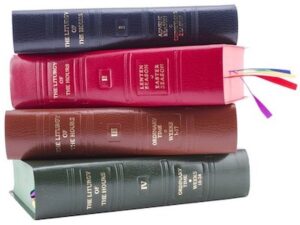

One of the very first things that I learned to do when I began to change my life was to begin keeping a gratitude journal. This incredibly simple practice can have a profound effect on one’s happiness and well being. I was introduced to the Divine Office by a lifelong friend who is a Catholic Priest. From time to time he has come to visit our family for a few days, and he always brings several beautifully bound large volumes with him for his daily prayers. I was fascinated and intrigued by all of the ribbons and the elaborate process involved, but thought of this prayer as a somewhat arcane practice, reserved for the clergy.

I was introduced to the Divine Office by a lifelong friend who is a Catholic Priest. From time to time he has come to visit our family for a few days, and he always brings several beautifully bound large volumes with him for his daily prayers. I was fascinated and intrigued by all of the ribbons and the elaborate process involved, but thought of this prayer as a somewhat arcane practice, reserved for the clergy.